“Yes, he’s alive,” the visiting priest answered his host as they sat out on the lawn, one summer day in 1970, overlooking the valley vista beyond them. “But he’s very, very sick.”

A pronounced pause of silence followed as the old man’s mind wandered away. The young cleric respectfully waited for his frail host to lead the conversation again.

“Did you say Monsignor Hickey is well, or is he sick?”

“He’s sick,” graciously repeated the guest, having no trace of impatience with the aged man’s forgetfulness. “He’s not at all well.”

They rose and walked a few paces. “That’s our little cemetery down there,” the senior priest lovingly noted for his guest, who was the first diocesan priest to visit him in many a year. But his memory and mind were failing. His voice was barely audible, and his speech a trifle slurred. What a dramatic contrast, the visitor must have thought, to the thunderous preacher of past years about whom he had heard so much!

Then once more the older Father, reminiscing on those earlier times, queried: “Is Monsignor Hickey well, or is he still sick?”

“He’s still sick.”

Father Leonard’s mind would drift away again, but only to come back as he remembered his guest. The young priest had come up from Harvard to visit him.

“If we had stayed in Cambridge, we would have converted at least a third of that place,” Father Leonard asserted confidently, his memory of those extraordinary years at the edge of “that place,” Harvard University, returning to him and rekindling his zeal.

“Father, we had two hundred converts,” the age-worn priest went on to boast proudly.

“Oh,” he lamented at length, “if only the Church would stand up today and say this is the one, true Church, and there is no salvation outside of her!”

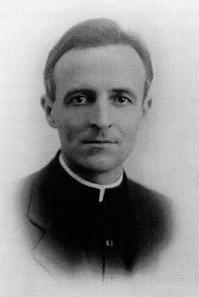

That was the quintessential Father Leonard Feeney, Founder of the Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, even in his waning years still championing the solemn truth in whose defense he had given and suffered so much.

To anyone knowledgeable of the sainted giants of Catholic history who had fought in defense of the Faith at whatever the personal costs, this would seem an apt observation of what Father Feeney was “trying to do.” The priest who offered it, however, clearly meant that he considered Father Feeney to be something less than a saint — probably even that the famed Jesuit poet, on this account, should have abandoned his hugely uneven struggle against the hierarchy and public opinion, for the sake of sparing his own reputation and the Church’s tranquility. After all, many a fellow priest who quietly agreed with Father Feeney’s doctrinal defense — and there were many — were saying much the same thing.

Great men whose individual endeavors have moved the world for the better are relatively few indeed throughout history’s long ages. This writer feels blessed personally to have known two whom he measures by that standard. Father Leonard Feeney was one, though I scarcely knew him on a personal level, and only in the last five years of his life, when his health and faculties were already diminished and noticeably failing more with each of those years.

The other man I esteem of true greatness left his stamp on political thought; and him I knew much longer and more intimately than, to my regret, Father Feeney.

Both men sacrificed all in the respective noble causes for which each fought. Neither, mind you, was in any sense a “revolutionary”; for each had championed, in disparate realms, only lofty ideals and profound truths which, in earlier, more honorable ages, had been uncontested. Yet the rage of vilification was so pandemic and so intense against both as to constitute living martyrdom for them.

The keenest heartache for each was inflicted not by their open enemies who persecuted them, but by those who were expected to defend their causes, yet did not.

I omit naming here my champion of political thought, who still evokes controversy many years after his death, only because doing so would be an unnecessary distraction in the present context. It is worth noting in this context, however, that, like Father Feeney, he had many who said of him, “I agree with what he says; I just don’t approve of his methods.”

To these I responded — and do forgive my abandoning the editorial “we” in favor of a more functional narrative “I,” as I’ll occasionally need to do in this account — “Well, if you do agree with what he says, if you truly understand the worthiness of the cause he’s undertaken and the enormity of the danger he’s fighting, just what methods would you approve? And, if you do know a better one, why don’t you put it into practice on your own?” Never did the question summon forth an intelligent reply. Almost always it was answered with silence.

I never presume to know the heart of any man. But I’m reasonably convinced that most who invoked this “I agree with what he says; I just don’t approve of his methods” position, did so more to excuse their own personal responsibility in an eminently worthy cause than genuinely to fault the “methods” of one who did have the courage and character to take it up.

And I certainly don’t know the heart of the university president mentioned above. Nor those of other contemporary priests at large who felt constrained to approve Leonard Feeney’s doctrinal defense sotto voce, while disparaging the man himself as not being enough a saint to defend it worthily. But one has to wonder, first, how a priest in Canada or elsewhere could fairly assess the sanctity, or its lack, in a Boston priest whose manner and methods had to be known mainly from public news sources. (As to the reliability of such news sources, a wag once said: “I wouldn’t even believe the page numbers in Life magazine unless I counted them myself!” Skepticism of this sort isn’t entirely undue, considering that Whittaker Chambers testified to being a high-level member of the Communist party during almost the same era, while serving as an editor of Time magazine.)

More importantly, if defending so foundational a Catholic dogma as extra ecclesiam nulla salus — “outside the Church there is no salvation” — against practically the entire Catholic hierarchy, were a challenge fit only for a saint, one must also wonder why fellow priests would not be more inclined to credit that to Father Feeney’s saintliness, rather than to his unsaintliness.

In truth, defending any solemn teaching of the Catholic Faith, whether against a single person denying it or against virtually the whole world repudiating it, is not a charge Our Lord reserved only for already accomplished saints. It is a duty incumbent upon every single Catholic, be he priest or layman — and fulfilling that duty itself is often the road to sainthood. Willful neglect of that duty is a grave sin, while rising to meet it is an act of supernatural merit. The greater the challenge against fulfilling the duty, the greater will be the eternal reward. Certainly one must objectively admit that, like St. Athanasius long before him, Father Feeney stood alone as a priest defending Catholic dogma against the world. For three decades! For that, if he was right and the world wrong, his eternal reward would have to be inestimable.

As a Boston Catholic born only a few years before the Boston Heresy Case burst forth, and who has come to appreciate the rich fullness and integral beauty of the Catholic Faith only since 1973, when I first met Father Feeney, I can speak personally to the state of Catholic education and Catholicism in general in those times and in that place. To Boston Catholics of my generation, and even of earlier ones, Catholicism was something one merely practised. And, at that, rather marginally. Almost the entire sum total of Catholic education I garnered in parochial schools was a collection of obligations and rules — thou-shalts and thou-shalt-nots. Observe them, and you save your soul. Additional meritorious points could be earned spiritually by reciting the rosary and attending extra Masses in Lent. In short, the Catholicism taught to me was more a skeleton — cold, colorless, inert, devoid of the flesh and blood, the vibrant, living body for which it was intended to give structural support.

To Father Feeney, the Catholic Faith was not a mere practice or code of laws. It was a lifestyle. Indeed, it was life, with all its glorious vitality, wonder and mystery. And it was a challenge. And that, perhaps, is what came to set him so far apart from the great mass of other Catholics like myself, and even from other priests. Little wonder so few among us practising Catholics understood the sanctity of his crusade. It is hoped, therefore, that the following glimpses at the life of Father Feeney — taken not from news sources, but from those who knew him personally and intimately as a priest and teacher — will help us come to understand him better, to revere him for his living martyrdom, and to cherish him as one of the Church’s courageous heroes.

At least from all I can infer as a latent disciple of his, there are really almost two distinct lives of Leonard Feeney, each set apart by roughly the midpoint of his earthly years. The first was that of a famed poet, essayist and lecturer who was widely esteemed, acclaimed and loved. The second was that of a brilliant theologian, inspiring apostle and heroic defender of Catholic truth who was even more widely ridiculed, persecuted and despised. Common to both lives was his priesthood and a prodigious intellect which, during the former one, seems to have left in him a restless anxiety to serve God more fruitfully, more meaningfully in some way not yet discoverable to him. And that, combined with God’s inscrutable Providence, is what I surmise gave birth to the latter life, the greater life, of Father Feeney. But let’s begin our look at both with the most logical starting point.

In his book, Survival Till Seventeen, a delightful collation of reminiscences from his childhood, Father Feeney reflected:

“Among the very few papers in my possession which might be honored with the dignity of being called ‘notes’ is the certificate of my birth.... It is such a decisive, laconic, frightening document, that I have often stared at it with something of the feeling one might have if he could tip-toe into his own nursery and find himself asleep in his own crib. The document remarks, concerning an existence which is indubitably mine:The Leonard half of that surviving union of family names was contributed by a petite, gentle, and lovely Irish girl — “like a little doll!” as Father Feeney, in later years, proudly quoted some “astute observer” as describing her. Before marriage at age eighteen, “Her name was Delia Agnes Leonard,” wrote Father Richard J. Shmaruk in the only extensive, if not entirely favorable, biography of Leonard Feeney of which we are aware, “but she never cared for her first name. She liked to be called Agnes.” Sister Mary Clare, one of Father’s long-time disciples who composed a much more favorable, if less extensive, biography after his death, describes Agnes Feeney as “a gentle, exquisite lady, simple and untutored,” and says “he idolized her.” Such that, had there been no Mother’s Day, one suspects he would have invented it just for her.“NAME OF CHILD: Leonard Edward Feeney“It was the original intention of my parents to give me no middle name, but by a combination of my father’s and my mother’s family names, to make my own a happy union of the two. The Edward was thrown in at Baptism in honor of my Uncle Edward, who was my sponsor, but it was thrown out later after we had satisfied him with this courtesy.”

“DATE OF BIRTH: Feb. 15, 1897

“SEX: Male

“COLOR: White

“PLACE OF BIRTH: 118 Adams Street, Lynn, Mass.

“FATHER’S NAME: Thomas Butler Feeney

“MOTHER’S NAME: Delia Agnes Leonard

The father, an Irish immigrant, likewise was of rather small stature, but possessed a gregarious personality that was larger than life. It may well have been that personality, that gift of charm for which the Irish are so well known, that led to Mr. Feeney’s highly successful career with Metropolitan Life.

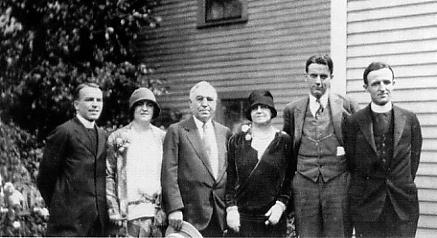

By 1909, the second tier of the Clan Feeney consisted of Leonard, Thomas Butler Jr., Eileen and John. (All three boys would eventually become priests.) That year the family took up residence in a spacious three-story house at 73 Lewis Street in Lynn, a dozen miles up the North Shore from Boston.

“When I went to school,” Father would write years later, “I came to believe that Leonard derived from the Latin words: leonis ardor, meaning ‘fierceness of a lion,’ and I was wont to boast of this signification. Some years later, however, I met a priest in Florence named Leonardo, and he told me that our name is taken straightforwardly from the Latin: leo and nardus, meaning ‘lion and spikenard,’ and rendered freely as ‘strength and fragrance’ or ‘strength and healing.’ However gracefully he put it, I was not pleased with the new translation. I preferred being a ‘wild lion’ to being a ‘sweet lion,’ and wish I had been left under my original illusion.”

But, in fact, one finds nothing about young Leonard that was wild. (The term might have more closely suited his younger brother. Tommy, a lovable and irrepressible prankster with a penchant for shinnying to the top of lampposts and climbing up the sides of large buildings. But even Tommy’s antics were wholly innocent.) No, Leonard was far more the quiet thinker than a “wild lion.” And one has only to read, in Survival Till Seventeen, his contemplative analogy of Gold Fish Pond and heaven to realize what a prodigious thinker he was, even as a young boy.

A serious and sensitive thinker young Leonard was by nature. But by force of environment a counterbalance was cultured in him and all the Feeney children. “Our house was always ablaze on Sunday evenings,” he wrote. ‘We invariably had at least three roomsful of visitors, and what with music, laughter and oratory, I do not know what the neighbors thought of us. It must have seemed as if the Feeneys were putting on a perpetual bazaar. As far as I can remember we never visited anybody. People always visited us.”

One did not just “visit” the Feeneys. Guests would have to furnish compellingly persuasive reasons for not being able to sleep over as well and partake of a hearty breakfast fare in the morning. Such was the generous hospitality there, that it would appear there really were no spare rooms in the large Feeney house. They seemed to be continually occupied, if not by guests, then by relatives or friends who had come on hard times; “and they lived with us until they either (a) died, (b) married, or (c) entered religion.”

“My father was an incorrigible cenobite,” the firstborn would record. He detested solitude and had a positive horror of silence. He delighted in noise in any form. He particularly liked to hear others sing. The worse you sang the more my father applauded, and the more he urged you to an encore.”

Guests had only one obligation in return for the famed Feeney hospitality: Almost as a matter of compulsion, they were expected to perform. Play an instrument, sing, recite poetry, tell stories — it didn’t matter, nor did the quality, just so long as they contributed. Under such house rules, therefore, the Feeney children by mandate had to develop talents for entertaining not the guests so much as Mr. Feeney himself. Leonard played the violin, and Tommy the clarinet. More than that, they early acquired oratorical arts and skills that would serve them well in their priestly careers.

As might also be imagined, the venue attracted a rich variety of personalities and characters. The careful study of which, I venture to guess, helped equip Leonard with one of the special charisma for which he was known as a priest: his uncanny ability to discern the character of others. Anyone who ever felt the powerful gaze of his penetrating, dark eyes knows exactly what I mean.

’You have to have a Catliolic education,” was more than Mr. Feeney’s conviction; it was a fundamental truth. And it’s said that he imparted it to others liberally. For his children Catholic education began at St. Joseph’s, the local parish school. “During Lent and the whole month of May,” Father Shmaruk writes, “they would make that trek of three-quarters of a mile six times in a single day.” The same source mentions: “Leonard and Tommy excelled in their studies at St. Joseph’s school.”

All three of Tom Feeney’s sons would go on to study at Boston College High School — “B.C. High,” as it is more familiarly known to Greater Bostonians. According to Father Shmaruk, Leonard was “one of the smartest boys in the class.” He “participated in school theatrical productions,” proving to be a “good actor.” And he was “active in debating and elocution competition.”

In the class ahead of Leonard’s was a young fellow named Jimmy. According to Father Shmaruk, Jimmy had had no parochial-school education before B.C. High. He was a product of the Boston Public School system, “and he had little to show for it except a long record for truancy. So he dropped out when he was fourteen to go to work. He was not unintelligent, however, and some priests ... convinced him ... to go back to school. Now, in his junior year at Boston College High School, the boy’s grades were so poor that the prefect of studies sent a letter to his father....”

“Jimmy had one saving grace,” Father Shmaruk continues. “His oratorical talents attracted attention at the school.” Those talents occasioned his competing in debate with our young man from Lynn. Jimmy’s full name was Richard James Cushing, later to become the Archbishop of Boston who censured Father Feeney. That high-school debate was when “Leonard Edward Feeney and Richard James Cushing matched wits for the first time. Leonard would brag to friends many years later that he had won that contest, and he’d joke that his opponent was finally taking his revenge....”

Leonard’s Jesuit teachers at B.C. High took careful notice of his academic prowess and had nurtured in him a vocation in the Society of Jesus. In September 1914, shortly after the death of Pope St. Pius X, he entered the Jesuit novitiate at St. Andrew-on-Hudson, near Poughkeepsie, New York. He received honors for his academic achievements, and was singled out as “a great prospect ... to keep an eye on.”

From childhood he had always been frail. During his novitiate, he grew ill from an ailment that evaded diagnosis and “lost a tremendous amount of weight.” He underwent surgery, in which part of his stomach was removed, and was allowed to return home to recuperate. He did recover somewhat before being called back to St. Andrew’s, but, in his own words, only to “about 49 or 50 per-cent” of normal. His overall health thereafter would never improve beyond that level.

Following philosophy and theology courses at Woodstock College in Maryland, he was assigned to Weston College near Boston, in 1927, to complete his seminarial training.

It was at Weston, that he was ordained, on June 20.1928, by the Jesuit Bishop Joseph N. Dinand. “On the following day,” Father Shmaruk writes, “he signed a statement [attesting] that he had taken the required oath against Modernism.” At the command of Pope St. Pius X, this Oath was required of all priests being ordained. Part of that oath read as follows: “I sincerely accept the doctrinal teaching which had come down from the apostles through the faithful Fathers in the same sense and meaning down to our own day. Therefore I wholly and entirely reject the false invention of the evolution of dogmas, whereby they pass from one meaning to a meaning other than that formerly held by the Church.” After Vatican II, as the new spirit of “ecumenism” swept through Church, the Oath against Modernism was suppressed, and priests were no longer required to take it.

“When he finished his courses at Weston in 1929,” Father Shmaruk chronicles, “he was chosen to spend a year in Europe studying ascetical theology at Saint Beuno’s in Wales.” He then was sent to Oxford to study English literature. Father Feeney would write; “There was a time when the Vatican forbade ... Catholic boys to go to Oxford or to Cambridge.” But already, so shortly after the passing of Pope St. Pius X, the times were changing. And so were the Jesuits.

Sister Mary Clare quotes one of his professors, Lord David Cecil, as having said: “I am getting more from my association with Leonard Feeney than he could possibly get from me.”

While still a seminarian, Leonard’s nationwide literary acclaim was already in the making. Periodicals such as Harper’s, Commonweal and America had published some of his verse during this time. His superior gave permission for the publishing of a collection of his poems. And his delightful book, In Towns and Little Towns, was published in 1927.

There was also the open letter to New York Governor Al Smith that he published in 1928. Smith had been defeated in his bid for the presidency that year, in what was decidedly a vote against the candidate’s unapologizing Catholicism, not his political platform. The published letter was entitled the “Brown Derby,” a reference to Smith’s famous hat which had become his trademark. In the letter, taking the initiative to serve as spokesman for American Catholics, Father commended the governor for standing by his Catholic convictions in spite of the cost: “Politically, it hurt you to be one of us. It ruined you. If only you could have disowned us somehow. If only you could have soft-pedaled the fact that you go to Mass on Sundays, if only you could have snubbed a few Catholic priests in public, or if only you could have come out with some diatribe against nuns and Religious Orders, or something of that sort, nice and compromising, you could have had the White House, garage and all, for the asking.”

By reply, Smith told Father, “I know of no article that has received such widespread publicity as that one. I was compelled to send to the publishing house for some copies, so many of my personal and intimate friends were asking me for them.”

Before his death years later, Al Smith honored Father Feeney with what was perhaps his most coveted earthly possession: his brown derby.

Sister Mary Clare wrote, “By 1934, Catholics in America began to realize he was a priest who had style, who had wit, who had words, and something to say with them. He was in demand for lectures at their colleges, and talks at their communion breakfasts in places like the Waldorf Astoria, and eventually was put on the radio Sunday nights. It was their hour, the ‘Catholic Hour.’ He complained that on Sunday nights a radio speaker had stiff competition from ‘contraltos, commentators, and comedians — none of which I am.’ He needn’t have worried. He held his audience spellbound from the beginning. His magnetic voice and dominant personality seemed to reach each one, singularly.”

Father Feeney, in fact, was the only substitute Bishop Fulton J. Sheen would have on his nationally broadcast radio program.

Meanwhile, Father’s writings had even become mandatory reading in many of America’s Catholic schools. In short, through his poems, his essays, his radio broadcasts, Father Leonard Feeney very quickly had become a national celebrity. Celebrity was something the Jesuit Society in America relished, when it redounded to the Society’s own prestige. And so, in 1931, Father was assigned to Boston College, where he would teach, and where he could write.

As a distinguished writer and lecturer, Leonard Feeney, S.J., well served the Catholic Faith he loved and practised so intensely. “His energy, his anxious, intense personality, his vigorous mind and character attracted those who loved the Faith as well as those who hated it,” as Sister Mary Clare attests. He regarded himself first and foremost as a priest, and disdained being call a “poet priest,” saying it gave the impression “of a poet who did a little priesting on the side.” He longed to be able to perform more priestly ministrations, and not merely in the quiet, polite, mild manner that suited New England Yankee tastes, but boldly, fervently, challengingly, after the example of St. Francis Xavier. The forum for free expression of thought that he had observed in London’s Hyde Park had fascinated him and sparked in him a novel notion: Why not set up a soapbox on Boston Common and preach Catholicism in the same manner! He approached his provincial with the idea: “He said, yes, I could, but he would have to ask Cardinal O’Connell for permission .... Two months later, I was sent to New York as [an] editor of America.’’

Since their suppression in 1773, the Jesuits, at least in the United States, have had a penchant for giving some of their institutions atypically non-Catholic names. Such as Georgetown University, instead of, say, St. Ignatius University; or Boston College, rather than St. Robert Bellarmine College; or Woodstock College, not St. Isaac Jogues College. Some see in this a hint of the murky, anti-apostolic, minimalist current within the American Church that Pope Leo XIII condemned, calling it Americanismus — “Americanism.”

America, though the title would never betray it, is a Jesuit national weekly published out of New York City. And having so popular a literary name as Leonard Feeney, S.J., on its masthead certainly had to have appealed to the Jesuits’ taste for prestige a lot more than letting him expound Catholic doctrine from a soapbox on Boston Common, only yards from the ears of Brahmin society living on Beacon Hill.

Arriving at America in 1936, Father applied himself fully and energetically as Literary Editor. By some accounts, however, he was not happy in the role. That would be understandable, since it only isolated him more when he yearned for greater priestly activity among the people. His prominence as an acclaimed literary figure, after all, was one which had been shaped more by ambitions of the Jesuit Society than of his own.

In this period, Sister Mary Clare noted, “he was moving freely and frequently in the highest circles of New York with well-known figures like Sinclair Lewis, Dorothy Thompson, Jacques Maritain, T.S. Eliot, Noel Coward, Fulton J. Sheen, and others.” He was, or would become, highly critical of such literati. So few were of his spirit. (One of those few, however, was the prominent Catholic historian, William Thomas Walsh, with whom he shared a close friendship and mutual respect.) Father Feeney “preferred people like taxi-cab drivers, dock-workers, janitors, and waiters,” Sister continues. ‘They were the simple of heart and he called them ‘the soundest of all metaphysicians and, under the influence of divine grace, the profoundest of all mystics.’ ”

He became increasingly displeased with America’s editorial policies, after its conservative editor-in-chief, Father F.X. Talbot, was quietly eased into obscurity, and Father John LaFarge assumed control. By 1940, according to Father Joseph Merrick, “Leonard Feeney didn’t have anybody at America who was too fond of him....” The tension and stress took their toll on Father’s already substandard health.

“The October 5, 1940 issue of America,” wrote Father Shmaruk in his unpublished biography, “listed his name among the members of its staff for the last time.” He was reassigned to the faculty of Weston.

Continue to Part II.